With agricultural supply chains focused on becoming carbon neutral by 2030 (CN30), farmers are under increasing pressure to reduce or offset their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

CN30 is a new and evolving space for farmers who are always on the look-out for practical solutions. So, what practical steps can farmers take as the space continues to evolve?

To help answer these questions, South West NRM engaged Nutrien Ag Sustainability Field Manager Kirsty Want (née Smith) to speak to livestock producers about their options at a recent workshop in Donnybrook.

The first step is to avoid distraction about the validity of methane emissions calculation methods. Methane typically accounts for about three-quarters of a livestock enterprise’s emissions. However, there is debate about whether the current calculation used to assign the global warming potential of biogenic (animal) methane is correct. Whether this calculation changes in the future or not, government, financial institutions and food processors are acutely aware of the impacts of methane and are looking to reward livestock producers who are making emission reductions.

Kirsty urges farmers not to get hung up on arguing how methane should be accounted, and instead focus on reducing it, because that is what the supply chain is looking for.

“Government policy is a big driver of emissions reductions, but the supply chain may have a bigger influence in the short term. Rabobank and the big four banks have signed the global Net-Zero Banking Alliance, which is committed to net-zero finance emissions by 2050…So while we may all hold different views on emissions, we need to remember, there is going to be no ‘opt out’ in this space. It’s coming whether we like it or not.”

The next step is to start measuring your baseline emissions so you know where you’re starting from. An average baseline may take several years to establish due to seasonal changes, so Kirsty says the best time to start measuring your emissions was ten years ago, but the next best time to start is today!

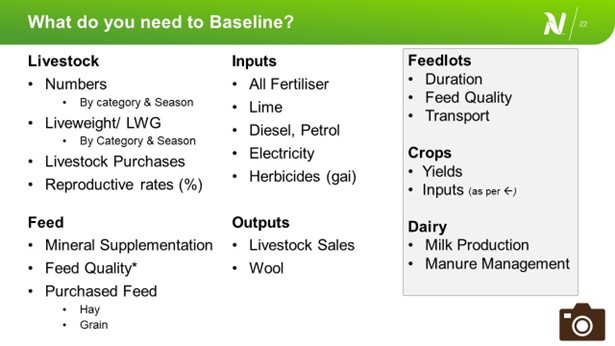

Measuring emissions is somewhat complicated, but Kirsty provided the information that livestock producers need to conduct a baseline calculation (see image below). There are several calculators now online and organisations like South West NRM can help producers to calculate their baseline.

The next step is to look for ways to reduce emissions.

“For livestock, there are things that we can do now that are all about maximising productivity. Best practice drives your emissions intensity down.”

Improving reproductive performance or fertility rate will be the number one biggest thing to do to drive down your emissions intensity.

“Conception rates in cattle you should be aiming for 80-90%. In sheep, it is really driven by lambing rate. For merinos, aim for 100-120%, and for crossbreds, 100-160%. Anything you can do to condition your breeding stock pre-conception and into pregnancy, and ensure lamb survival, is going to lower your emissions intensity.”

The next stage is to maximise post-weaning growth rate. Kirsty used a scenario from the Eastern states where autumn-born steers are raised for a 650kg slaughter weight.

“If you don’t get that weight in their second spring and you have to carry them through another summer or autumn you’ll experience possible weight loss and need to supplementary feed for another 5-8 months. This costs around $125 per head in feed and 1 tonne of carbon dioxide equivalents per animal.”

Kirsty then followed up with another scenario to show the importance of genetics to achieve better feed conversion.

“If we have two steers fed to maintain the same rate of weight gain, with a 1.3kg (dry matter) difference in daily intake, over a year this equates to an additional 463kg of feed and 711kg of CO2e difference.”

There are also things that we can do now to reduce emissions in existing animals through feed additives.

“With fats and oils you can have about 20% reduction, and tannins can reduce emissions by around 10-15%. Nitrate supplementation gives a 12-16% reduction, but there are obviously risks associated with it. Bovaer® is an example of a methane inhibitor, but costs are relatively high, so given the ACCU (Australian Carbon Credit Units) price right now, it is not commercially viable.”

The methane inhibitor we have all heard of is red seaweed, Asparagopsis, which contains bromoform. It has been shown that when included in every kilogram of feed that a cow consumes, it can reduce methane by over 80%. Obviously, the issue is that we can’t always include it in the feed ration. In dairy systems, where they’re feeding only twice a day, they have had around a 40% reduction in daily emissions.

Kirsty says that Asparagopsis may become available in a lick block or through other forms. However, there are growing concerns around bromoform in the atmosphere and other unknowns such as “can the rumen microbiome become resistant to it?”

There is no doubt that lots of work still needs to be done. But in the meantime, farmers should start measuring their on-farm emissions so they can establish a reliable baseline. That way, the reductions that they do eventually make can be recorded and recognised by both the public and the supply chain.

This project is delivered by South West NRM for the Landcare Farming Program, a joint partnership between Landcare Australia and the National Landcare Network, funded by the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program, and supported by Western Beef Association Inc.